Voronoi Fracture and Destruction

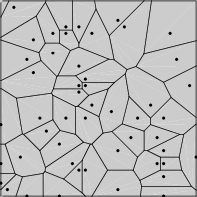

To simulate the destruction of an object in 2D or 3D, an algorithm called Voronoi fracturing (or shattering) exists. It uses a mathematical concept called Voronoi diagram, hence its name. A Voronoi diagram describes how to partition a space from a set of points into regions, called cells. The cells are guaranteed to be convex and no overlapped, and will be the shards of the fracture. You can see a representation in 2D below.

(Source)

The algorithm and implementation which is explained in this chapter are extensively adapted from the demo VoronoiFracture from Bullet Physics.

The approach

The algorithm works using 3D planes. From a 3D mesh, it takes the faces (triangles) and turn them into planes, represented by their equations. The idea is as follows: each shard (cell) is created by taking a Voronoi point, then create more planes, located at half distance between this current point and other ones, in order to generate the boundaries of this cell. The process is repeated for each point.

The pseudo code is shown below (adapted from the forum post of the demo author).

planes = collection of source object faces represented as plane equations

foreach current_point in voronoi_cell_points

copy planes

foreach other sorted_point by distance from current_point

if distance > max_distance

break # rest of sorted points too far, we’re done with this current_point

add new plane to planes, normal and distance = (sorted_point - current_point) / 2

collect vertices (3-plane intersections) by planes that fall inside all planes only

delete planes that fell outside

max_distance = (furthest vertex from current_point) * 2

we now have vertices and/by planes for one voronoi 3D shard,

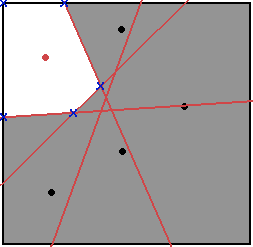

process vertices by plane to get faces and edgesFor example, for 5 Voronoi cell points, a 2D representation of the algorithm at the end of one iteration (the outer foreach loop) is shown below. A shard is generated and is represented by the white area. The red point is the current_point, the black ones are the other Voronoi points (which are sorted_points), the black and red lines represent the planes. The blue X represent the vertices at planes intersections. Note that the intersections which are outside the shard are not kept. In 3D, theses intersections would be formed by 3 planes.

This is a brute force method because it considers all Voronoi points, not only the neighbours. Another approach is to compute the Delaunay tetrahedralization, which connects points with tetrahedrons. From it, the Voronoi diagram can be extracted, since it is its dual graph. But this approach is not discussed here, since the method detailed here does not use Delaunay tetrahedralization.

The implementation

The implementation is adapted from the VoronoiFractureDemo.cpp source code. Assuming that the source mesh and the random Voronoi points are initialized, we begin with creating a function, voronoiMeshShatter(), that takes as arguments the points, the mesh (defined by vertices and triangles indices), its position and rotation. The 2 other parameters here (the density and the world, as a cutom class) are not important for the shattering algorithm.

void Voronoi::voronoiMeshShatter(

const btAlignedObjectArray<btVector3>& srcPoints,

const btAlignedObjectArray<btVector3>& verts, const btAlignedObjectArray<int>& indices,

const btQuaternion& rot, const btVector3& pos,

btScalar matDensity, World& world) {

// srcPoints define voronoi cells in local space (avoid duplicates)

// verts = source mesh vertices in local space

// indices = source mesh vertices indices composing each triangle

// rot & pos = source mesh quaternion rotation and translation

// matDensity = Material density for voronoi shard mass calculation

//…

}Meshes are generally described in local space (the origin is at the center of its vertices), as it is the case here. THe points are also in local space. We will convert them to world space.

// Convert verts to world space

int numverts = verts.size();

chverts.resize(numverts);

for (i=0; i < numverts; i++) {

chverts[i] = quatRotate(rot, verts[i]) + pos;

}

// Convert points to world space

int numpoints = srcPoints.size();

points.resize(numpoints);

for (i=0; i < numpoints; i++) {

points[i] = quatRotate(rot, srcPoints[i]) + pos;

}

sortedVoronoiPoints.copyFromArray(points);

Plane representation

We need to get the planes formed by the faces of the mesh. But how to represent a plane? It can be seen as an cartesian equation ax + by + cz = d where a, b, c and d are the 4 parameters. The vector (a, b, c) represent the normal, the scalar d represents the distance. These values can be stored in the Bullet’s btVector3, which has a “hidden” 4th value that can be accessed with the [] operator, like this: v[3].

Since the mesh is composed of triangles, the planes can be found using some geometry. If v0, v1, v2 are the corner vertices of a triangle, the formulas in pseudo-code:

normal = ( (v1 - v0).cross(v2 - v0) ).normalize();

distance = normal.dot(v0);

The actual code is:

// Get convexPlanes from triangles

int v0, v1, v2; // vertices

for (i=0; i < indices.size();) {

v0 = indices[i++];

v1 = indices[i++];

v2 = indices[i++];

// plane: 4 values stored in btVector3, as equation ax + by + cz = d

// (4th value accessed as plane[3])

plane = (chverts[v1]-chverts[v0]).cross(chverts[v2]-chverts[v0]).normalize();

plane[3] = plane.dot(chverts[v0]);

convexPlanes.push_back(plane);

}

Loop

We that the mesh and points are prepared, we can start to create the cells. To do this, the Voronoi points are taken one by one with a loop.

// For each voronoi point

for (i=0; i < numpoints; i++) {

curVoronoiPoint = points[i];

//…

}During the iteration, we will loop over the other points, sorted by the distance to the current point. Thus, we start with the point that is the nearest, then go to the next nearest, and so on. We stop when the distance to the next point is greater than a limit. But before that, we will make the calculations of the planes distances easier by shifting the their equations relatively to the current point.

planes.copyFromArray(convexPlanes);

// Shift all planes relative to current point

for (j=0; j < numconvexPlanes; j++) {

planes[j][3] -= planes[j].dot(curVoronoiPoint);

}

And we sort the points by distance.

maxDistance = SIMD_INFINITY;

// Sort all points by distance from current point

sortedVoronoiPoints.heapSort(pointCmp());

The comparator pointCmp() must be defined elsewhere. Note that curVoronoiPoint also need to be declared outside in order to be accessed from this comparator’s scope.

static btVector3 curVoronoiPoint;

// Comparator to sort planes by distance from curVoronoiPoint

struct pointCmp

{

bool operator()(const btVector3& p1, const btVector3& p2) const

{

float v1 = (p1-curVoronoiPoint).length2();

float v2 = (p2-curVoronoiPoint).length2();

bool result0 = v1 < v2;

return result0;

}

};

Back to the voronoiMeshShatter() function, we can now iterate through the other points, in order to generate a plane at half way between the current and the other point. In the previous 2D sketch, this plane is one of the red lines around the shard. At the same time we can check the distance limit. If this limit is reached for this point, it is for the next because the points are sorted.

for (j=1; j < numpoints; j++) {

// Create plane at half distance from current and other point

normal = sortedVoronoiPoints[j] - curVoronoiPoint;

nlength = normal.length();

if (nlength > maxDistance) // quit if point is too far

break;

plane = normal.normalized();

plane[3] = nlength / btScalar(2.);

planes.push_back(plane);

With this new plane added to the planes list, we generate the vertices at the intersection of 3 planes.

// Get vertices by 3 planes intersection, inside all planes

getVerticesInsidePlanes(planes, vertices, planeIndices);

if (vertices.size() == 0)

break;

numplaneIndices = planeIndices.size();

The helper function getVerticesInsidePlanes() is used. It takes the planes as in parameters (input) and vertices and planeIndices as out parameters (returned values). vertices are the intersections of 3 planes and which are on the “right” side, (that is, not outside the shard). planeIndices are the indices of the planes that gave the vertices. After this, the number of vertices that consitute the shard may have been reduced to zero. In this case, we are done, the shard is empty and can leave the loop for the next shard.

Otherwise, some planes may have not been involved. These planes are no longer part of the shard, thus they are not useful anymore. We remove them with the following code.

// Discard other planes

if (numplaneIndices != planes.size()) {

planeIndicesIter = planeIndices.begin();

for (k=0; k < numplaneIndices; k++) {

if (k != *planeIndicesIter)

planes[k] = planes[*planeIndicesIter];

planeIndicesIter++;

}

planes.resize(numplaneIndices);

}

We end the inner loop by updating the distance limit (the one that determine when to stop generating a shard).

// Update maxDistance = max vertice distance * 2

maxDistance = vertices[0].length();

for (k=1; k < vertices.size(); k++) {

distance = vertices[k].length();

if (maxDistance < distance)

maxDistance = distance;

}

maxDistance *= btScalar(2.);

}

if (vertices.size() == 0)

continue;

After this loop ends, we have all the vertices needed for the shard to be created. We do so first by using a btConvexHullComputer object to generate edges and faces of the object.

convexHC->compute(&vertices[0].getX(), sizeof(btVector3), vertices.size(),0.0,0.0);

Then, for a better physics behaviour, we need to determine the center of mass of it. Indeed, Bullet assumes that the origin of each object is its center of mass.

// Calculate volume and center of mass (Stan Melax volume integration)

int numFaces = convexHC->faces.size();

btScalar volume = btScalar(0.);

btVector3 com(0., 0., 0.);

for (j=0; j < numFaces; j++) {

const btConvexHullComputer::Edge* edge = &convexHC->edges[convexHC->faces[j]];

v0 = edge->getSourceVertex();

v1 = edge->getTargetVertex();

edge = edge->getNextEdgeOfFace();

v2 = edge->getTargetVertex();

while (v2 != v0) {

// Counter-clockwise triangulated voronoi shard mesh faces (v0-v1-v2) and edges here…

btScalar vol = convexHC->vertices[v0].triple(convexHC->vertices[v1], convexHC->vertices[v2]);

volume += vol;

com += vol * (convexHC->vertices[v0] + convexHC->vertices[v1] + convexHC->vertices[v2]);

edge = edge->getNextEdgeOfFace();

v1 = v2;

v2 = edge->getTargetVertex();

}

}

com /= volume * btScalar(4.);

volume /= btScalar(6.);

// Shift all vertices relative to center of mass

int numVerts = convexHC->vertices.size();

for (j=0; j < numVerts; j++) {

convexHC->vertices[j] -= com;

}Finally, the rigid body is created and added to the world.

// Create Bullet Physics rigid body shards

btCollisionShape* shardShape = new btConvexHullShape(&(convexHC->vertices[0].getX()), convexHC->vertices.size());

shardShape->setMargin(CONVEX_MARGIN); // for this demo; note convexHC has optional margin parameter for this

btTransform shardTransform;

shardTransform.setIdentity();

shardTransform.setOrigin(curVoronoiPoint + com); // Shard’s adjusted location

btDefaultMotionState* shardMotionState = new btDefaultMotionState(shardTransform);

btScalar shardMass(volume * matDensity);

btVector3 shardInertia;

shardShape->calculateLocalInertia(shardMass, shardInertia);

btRigidBody::btRigidBodyConstructionInfo shardRBInfo(shardMass, shardMotionState, shardShape, shardInertia);

RigidEntity* entity = world.createRigidEntity(shardRBInfo);

entity->getMesh().setColor(0, 0, 1);

cellnum ++;

}Helper function getVerticesInsidePlanes()

We mentionned this function earlier in the code but did not detailed it, thus here it is. This function takes all planes 3 by 3. For each of these triplets, if they are not parallel, it computes the intersection. It stores the intersected point and the corresponding plane indices only if the point is inside all the total planes. The definition of the function is provided below.

void Voronoi::getVerticesInsidePlanes(const btAlignedObjectArray<btVector3>& planes,

btAlignedObjectArray<btVector3>& verticesOut,

std::set<int>& planeIndicesOut)

{

// Based on btGeometryUtil.cpp (Gino van den Bergen / Erwin Coumans)

verticesOut.resize(0);

planeIndicesOut.clear();

const int numPlanes = planes.size();

int i, j, k, l;

for (i=0;i<numPlanes;i++)

{

const btVector3& N1 = planes[i];

for (j=i+1;j<numPlanes;j++)

{

const btVector3& N2 = planes[j];

btVector3 n1n2 = N1.cross(N2);

if (n1n2.length2() > btScalar(0.0001))

{

for (k=j+1;k<numPlanes;k++)

{

const btVector3& N3 = planes[k];

btVector3 n2n3 = N2.cross(N3);

btVector3 n3n1 = N3.cross(N1);

if ((n2n3.length2() > btScalar(0.0001)) &&

(n3n1.length2() > btScalar(0.0001) ))

{

btScalar quotient = (N1.dot(n2n3));

if (btFabs(quotient) > btScalar(0.0001))

{

btVector3 potentialVertex =

(n2n3 * N1[3] + n3n1 * N2[3] + n1n2 * N3[3]) *

(btScalar(1.) / quotient);

for (l=0; l<numPlanes; l++)

{

const btVector3& NP = planes[l];

if (btScalar(NP.dot(potentialVertex))-btScalar(NP[3]) >

btScalar(0.000001))

break;

}

if (l == numPlanes)

{

// vertex (three plane intersection) inside all planes

verticesOut.push_back(potentialVertex);

planeIndicesOut.insert(i);

planeIndicesOut.insert(j);

planeIndicesOut.insert(k);

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

Complete source

The code is provided in the Voronoi class of the project source code.